How can minorities of regular individuals overturn social conventions?

Higher-order naming game: combining group dynamics ans social influence

Ph by Markus Spiske

Ph by Markus Spiske

Our study “Group interactions modulate critical mass dynamics in social convention” is out on Communications Physics!

How can minorities of regular individuals overturn social conventions? The theory of critical mass argues that apparently stable social conventions can be overturned by a minority of committed individuals if such minority reaches a critical size. Several studies have focused on identifying this critical size.

Qualitative studies of gender conventions in corporate leadership roles have hypothesised that a critical mass of 30% of the population is necessary in order for the tipping point to be reached. Related observational work on gender research has proposed a higher critical mass size approaching 40% of the population.

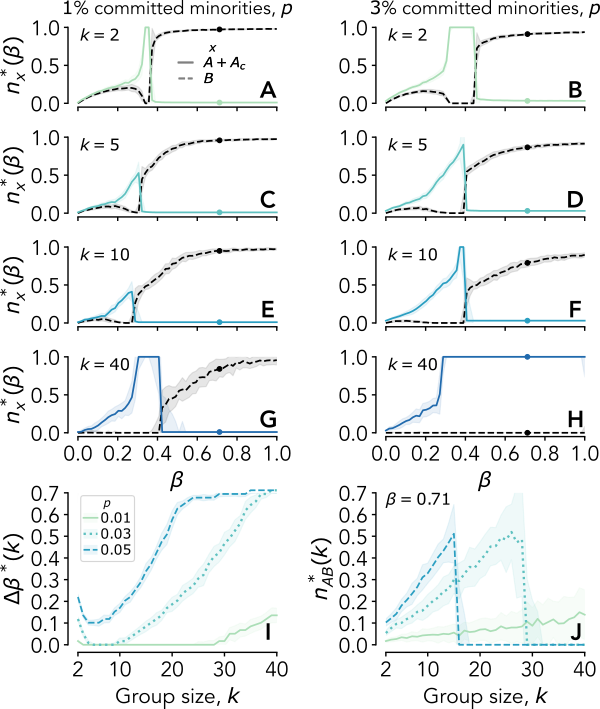

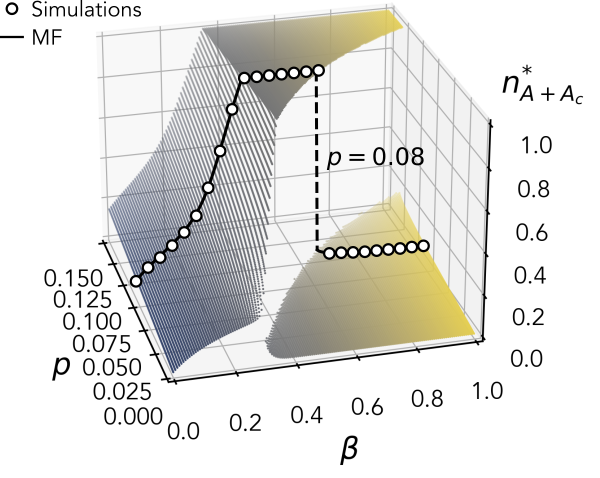

Quantitative support to the tipping points dynamics has come from the naming game model for social convention, where a critical mass of 10% was shown to be able to induce norm change. Subsequent generalisations showed how the threshold can vary between 10% and 40% of the population. Finally, controlled experiments of social coordination have brought empirical evidence for tipping points in the dynamics of social conventions, finding a critical threshold of 25% of the population, as theoretically predicted by a best response naming game model.

All theoretical models and empirical studies existing so far have considered minority groups of fully committed individuals, i.e., individuals who will not adopt majoritarian conventions under any circumstances. In this light, even 10% of the population, the smallest threshold obtained thus far, can hardly be considered a “small” group. Numerous observations suggest that even groups counting just tens of committed individuals, and not significant fractions of the population, may trigger abrupt social and normative change. Social movements offer several examples in this sense. So… where does the critical mass itself come from?

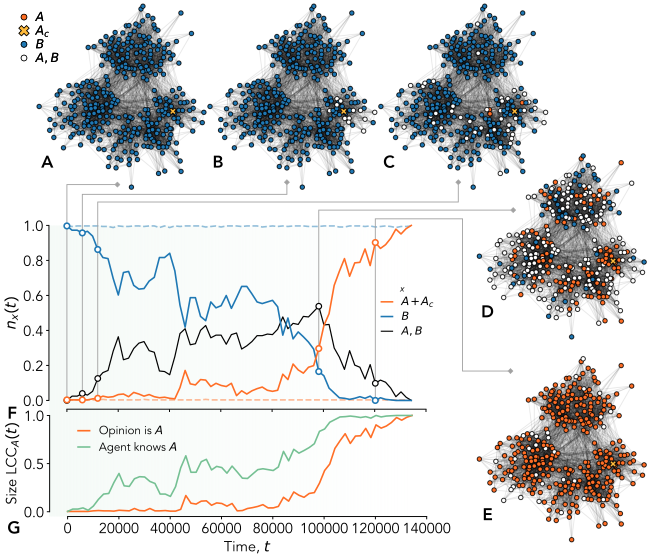

In this new work, together with G. Petri, A. Baronchelli and A. Barrat, we give a mechanistic explanation of how such small minorities can emerge. In particular, we show that the critical mass required to induce norm change is dramatically reduced when non-committed members of the population are less susceptible to social influence than previously assumed.

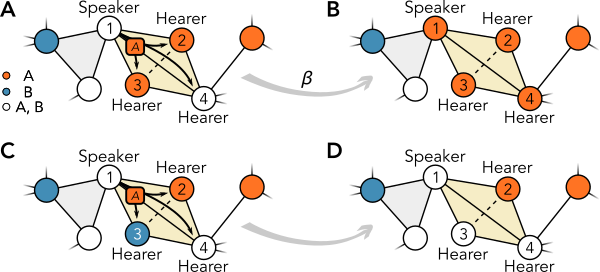

We adopt the Naming Game framework, already used to determine the range of 10% to 40% critical mass thresholds, and admit the possibility that individuals may be reluctant to let go of alternative conventions even when they successfully manage to coordinate with one another on a specific norm. We control this through a global communication efficiency parameter $\beta \in [0,1]$. This generalises the standard naming game model where a successful coordination is followed by a certain and exclusive adoption of the norm that allowed the coordination.

We inform the model with real-world data concerning the structure of the social networks and of the microscopic interactions, considering both pairwise and group meetings. This implies using a higher-order representation beyond pairwise interactions, as the one offered by hypergraphs.

We show that results hold in a significant region of the parameters and on all the considered real and artificial social structures. In addition, we clarify the role of group interactions showing a non-trivial dependency of the long term dynamical output with the group-size (non-monotonicity is observed). We also provide an analytical mean-field description of the model and confirm its accuracy against Monte Carlo simulations.

Our findings reconcile the numerous observational accounts of rapid change in social conventions triggered by committed minorities with the apparent difficulty of establishing such large minorities.

In this scenario, clarifying the microscopic mechanisms driving this process is key to gain a better understanding of our society and to design possible interventions aimed at contrasting undesired effects (see recent studies about social media infiltrations by the Chinese government).

On the other hand, understanding how policy can create tipping points where none exist and how it can push the system past the tipping point are fundamental questions whose answer might change the way in which we address major societal challenges, such as accelerating the post-carbon transition or contrasting vaccine-hesitancy.