Temporal group interactions in social systems

How do groups form and evolve? How do individuals navigate these group structures?!

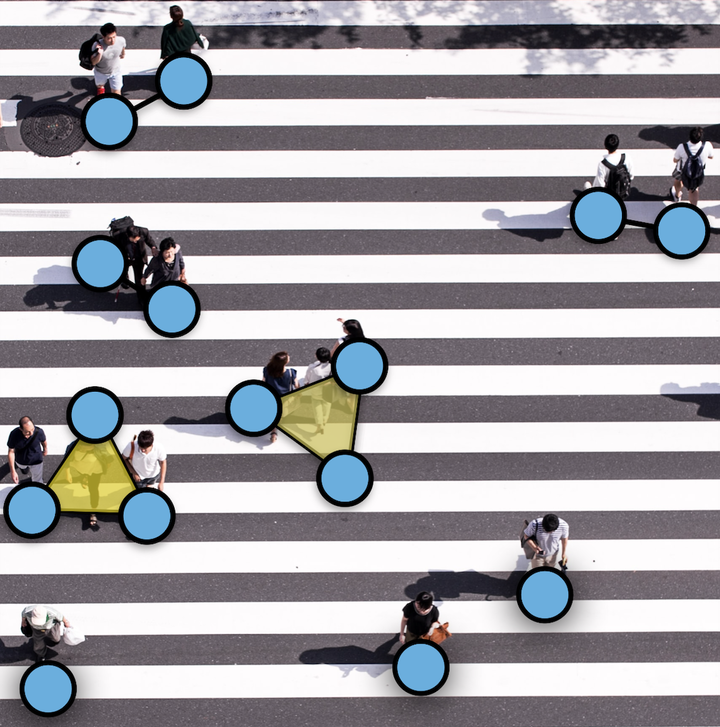

Based on ph by Ryoji Iwata

Based on ph by Ryoji Iwata

Our study on “The temporal dynamics of group interactions in higher-order social networks”, together with M. Karsai and A. Barrat, is out in Nature Communications! —-> [ link to arXiv] - [ link to Nature Communications]

The structure and behaviour of many social systems are shaped by the interactions among their individuals. The typical approach in social network analysis consists in representing individuals as interacting in pairs, while many human interactions involve groups of many different sizes.

Our everyday social path is in fact a succession of these group events that involve different numbers of peers, from walking alone or having a coffee with a friend, to engaging in meetings or group conversations at work or during social gatherings.

Why do we care about groups?

On the one hand, there is a foundational reason. To obtain meaningful insights from a system, choosing an appropriate representation is a crucial step that cannot be overlooked. Since the building blocks of many —not just social— complex systems are intrinsically non-pairwise, there is often a need for higher-order approaches. Hypergraphs are thus natural candidates to move system descriptions beyond dyadic relationships and effectively map relationships between any number of units (see also this post).

On the other hand, letting individuals interact in complex groups can have phenomenological consequences. Groups can lead to critical mass effects in social contagion and social dilemmas, sustain epidemics, accelerate the formation of consensus and help minorities of committed individuals to overturn the status quo (see also this post).

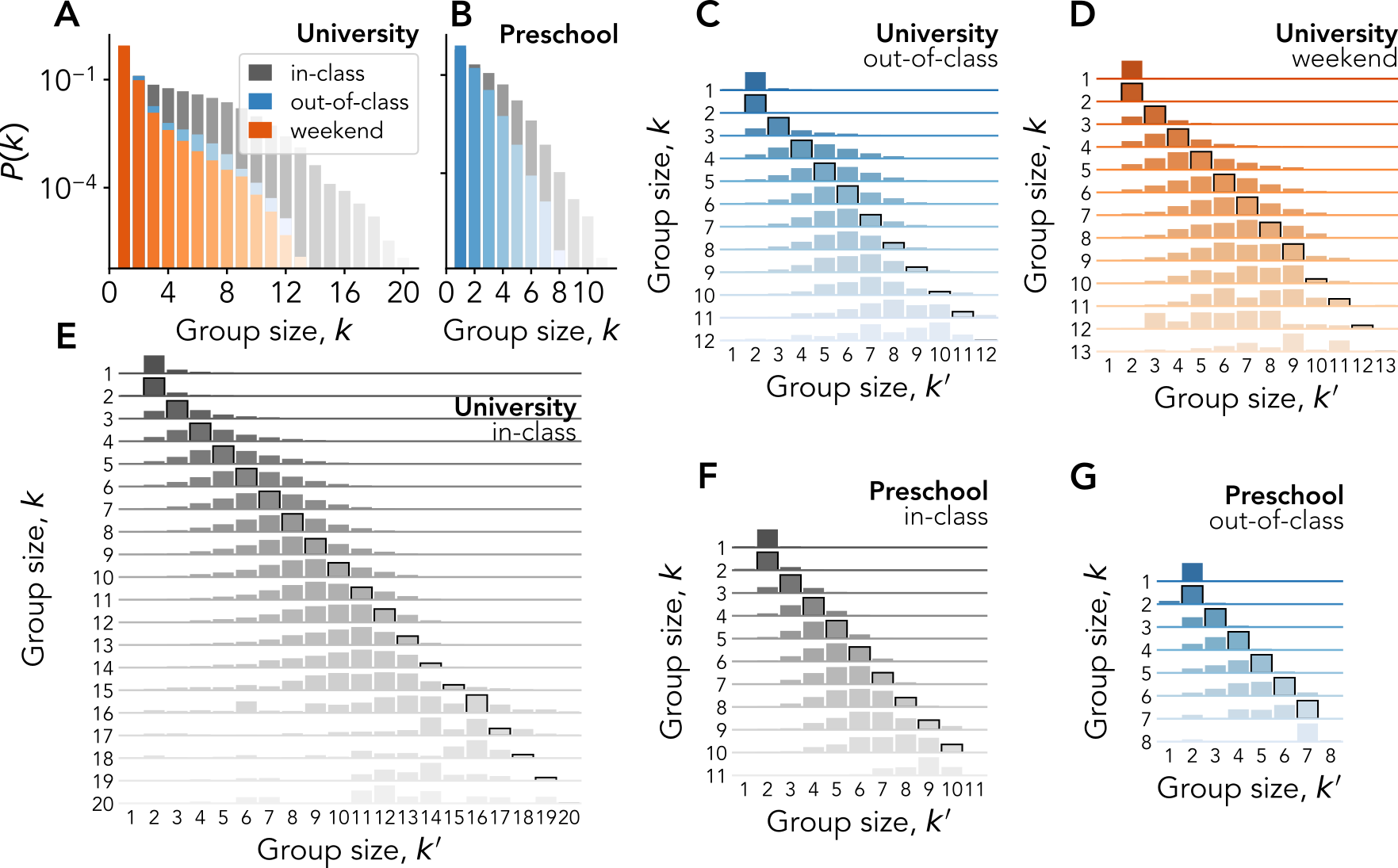

Recent empirical studies on co-authorship data, face-to-face, and online interactions have shown that groups may appear in heterogeneous size (order), can change dynamically, or exhibit complex hierarchical and nested structures. Group size is indeed a crucial factor that determines a group’s sociological form and its ability to sustain a single conversation —leading to the phenomenon known as schisming.

Most studies on group formation and structure, however, do not take into account the temporal evolution of the underlying social systems, characterised by patterns of memory, burstiness, and temporal correlations. These complex patterns are the results of microscopic individual-level decisions, ultimately shaping the emergence of collective behaviours.

Understanding these mechanisms —how these groups form, evolve, and how people move across groups— is essential to better characterise the emerging group dynamics and to better model biological contagion or transfer of social norms and information.

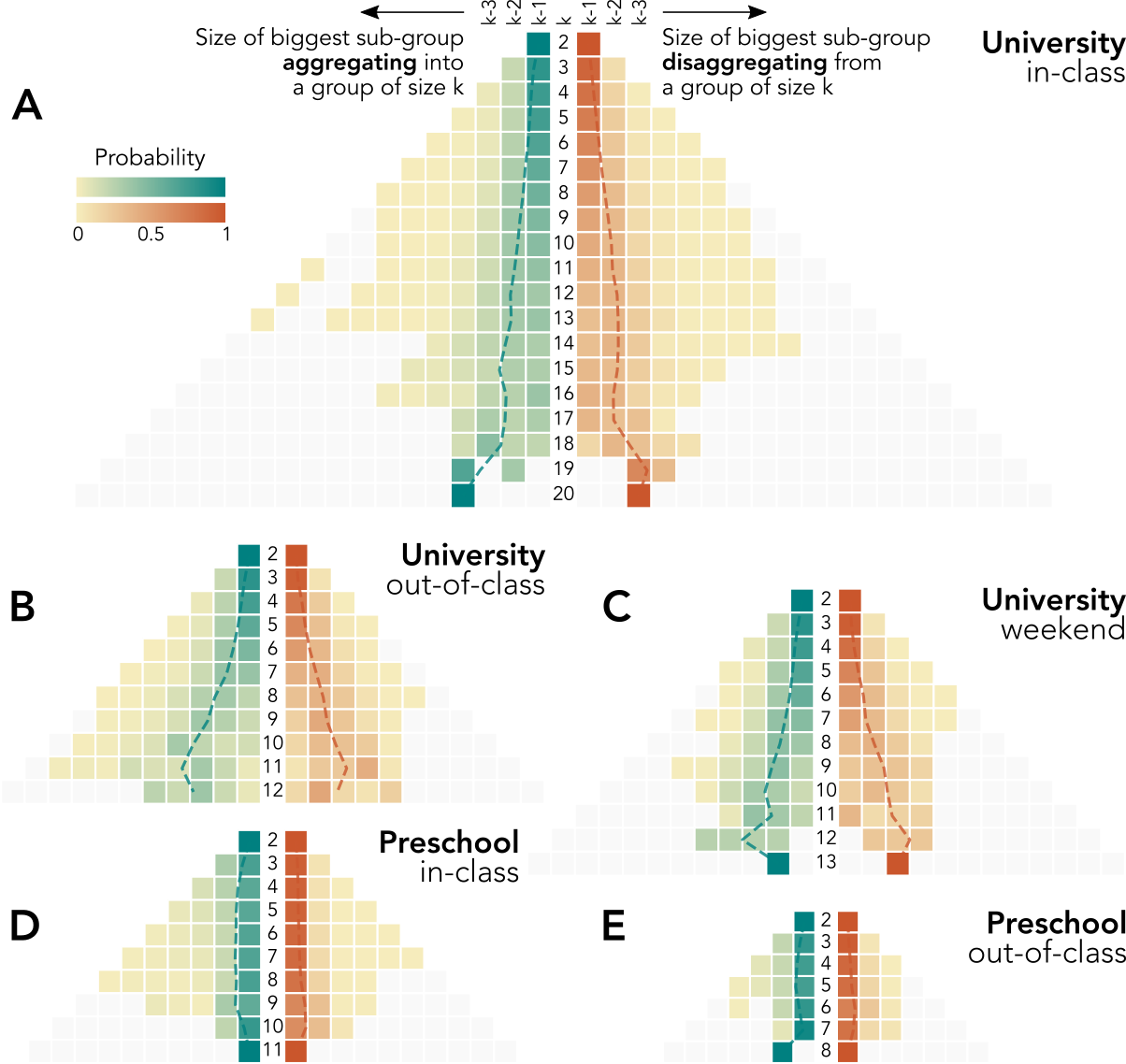

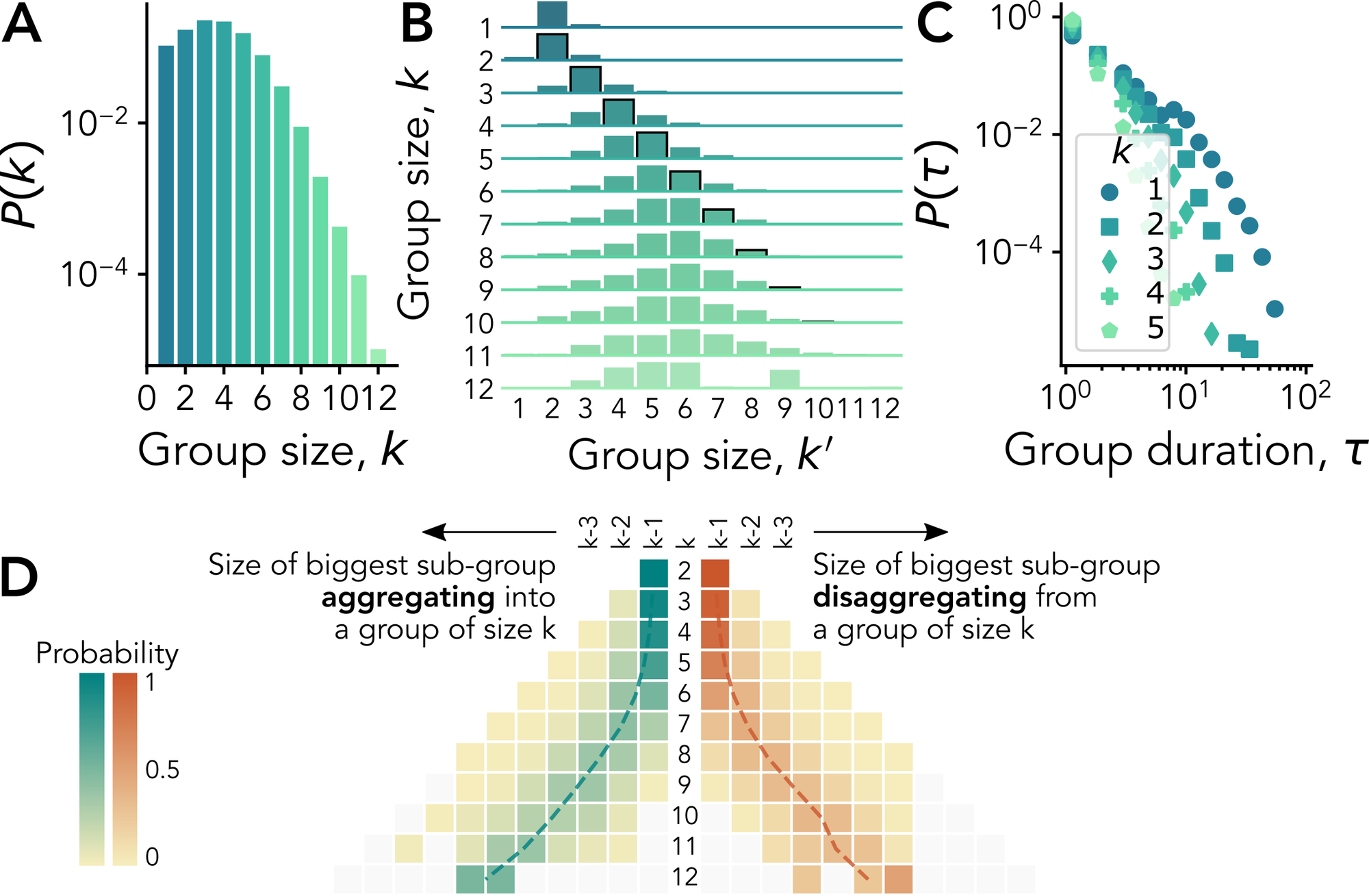

In this new study, together with M. Karsai and A. Barrat, we study the temporal dynamics of groups through empirical traces of social interactions. Leveraging two publicly-available data sets of temporally-resolved human interactions among preschool children and university students, we highlight complex mechanisms of group dynamics both at the node and at the group level.

At the node level, we follow how individuals move across groups of different sizes, finding that the main dynamical patterns of group-change are independent from the nature and context of interactions (due to age and setting constraints).

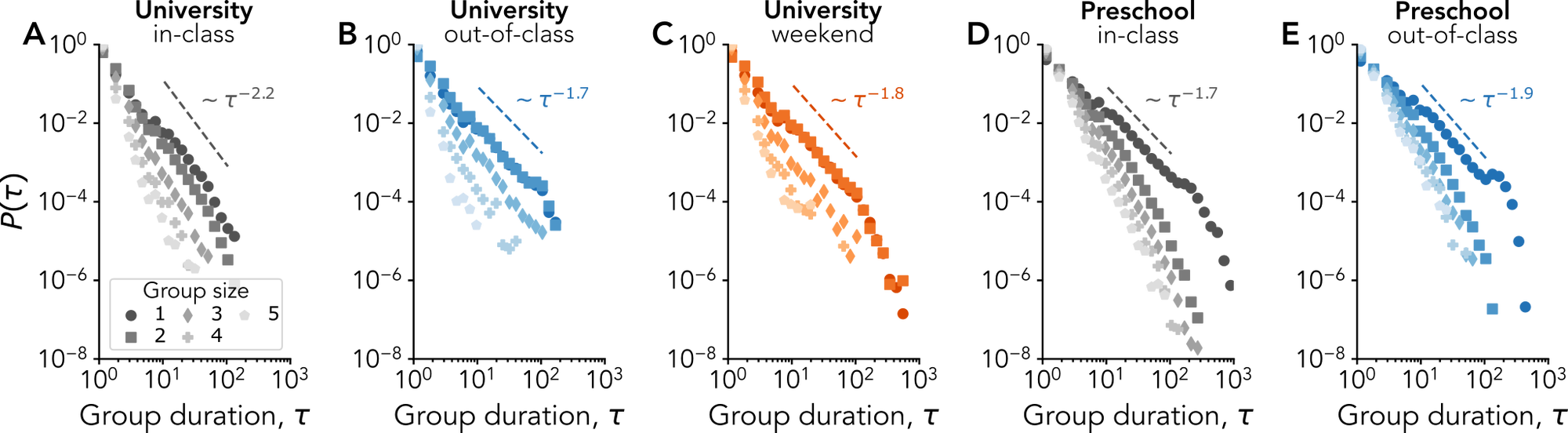

Shifting the focus to the groups, we analyze the statistics of group duration. Whether students interact during classes, in the other spaces of the university, or elsewhere during the weekend, the distributions of their group interactions depend on the group size in a similar way, with long-gets-longer effects.

While the individual point of view adopted is useful to understand how people move between group sizes, we still need to understand the impact of these individual changes on the sizes of the groups. For instance, large groups tend to have shorter lives, but how do they break up? Similarly, how do they grow? Indeed, a group might appear due to the fusion of two pre-existing groups of comparable sizes —like water droplets that merge after overlapping due to surface tension—, or from a gradual process due to the integration of one individual at a time.

We thus follow the members of each group before the group’s birth and after its break-up, pooling together the results of groups of the same size. For small group sizes, both group aggregation and disaggregation tend to happen gradually from or to groups of similar sizes. The picture for larger groups suggests instead a partially hierarchical dynamical mechanism according to which individuals first engage in relatively small groups that then aggregate and form bigger ones. A symmetric process takes place when large groups dismantle.

Finally, we propose a synthetic hypergraph model describing how nodes form groups and navigate between groups of different sizes. Informed by empirical data, the model reproduces the non-trivial dynamics of group changes, and could be used to generate synthetic substrates for studying the impact of higher-order temporal interactions on dynamical processes.

Taken together, our results hint at common robust mechanisms determining group formation and evolution. Our study represent a further step in understanding the social dynamics of higher-order interactions, stressing the importance of considering their temporal aspect.